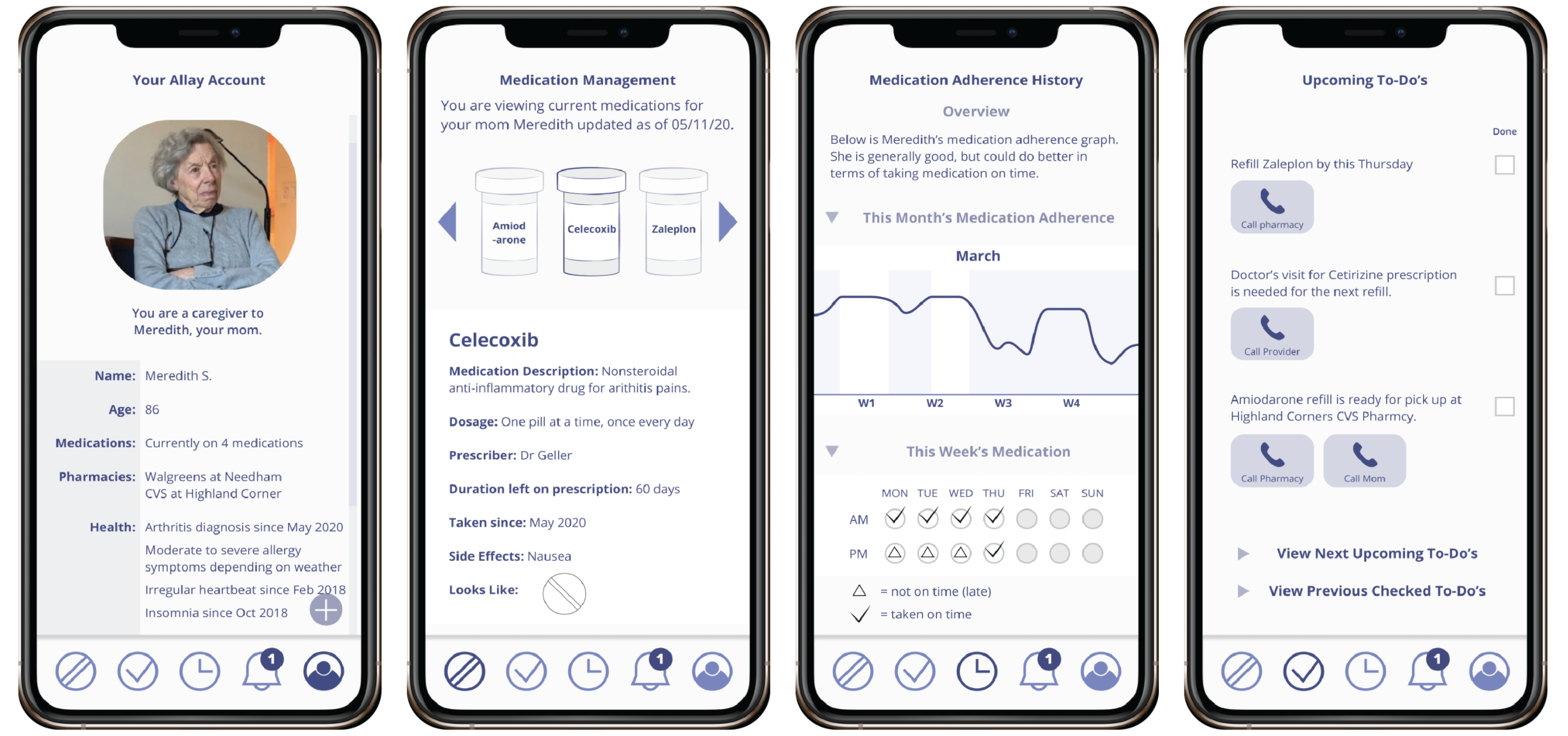

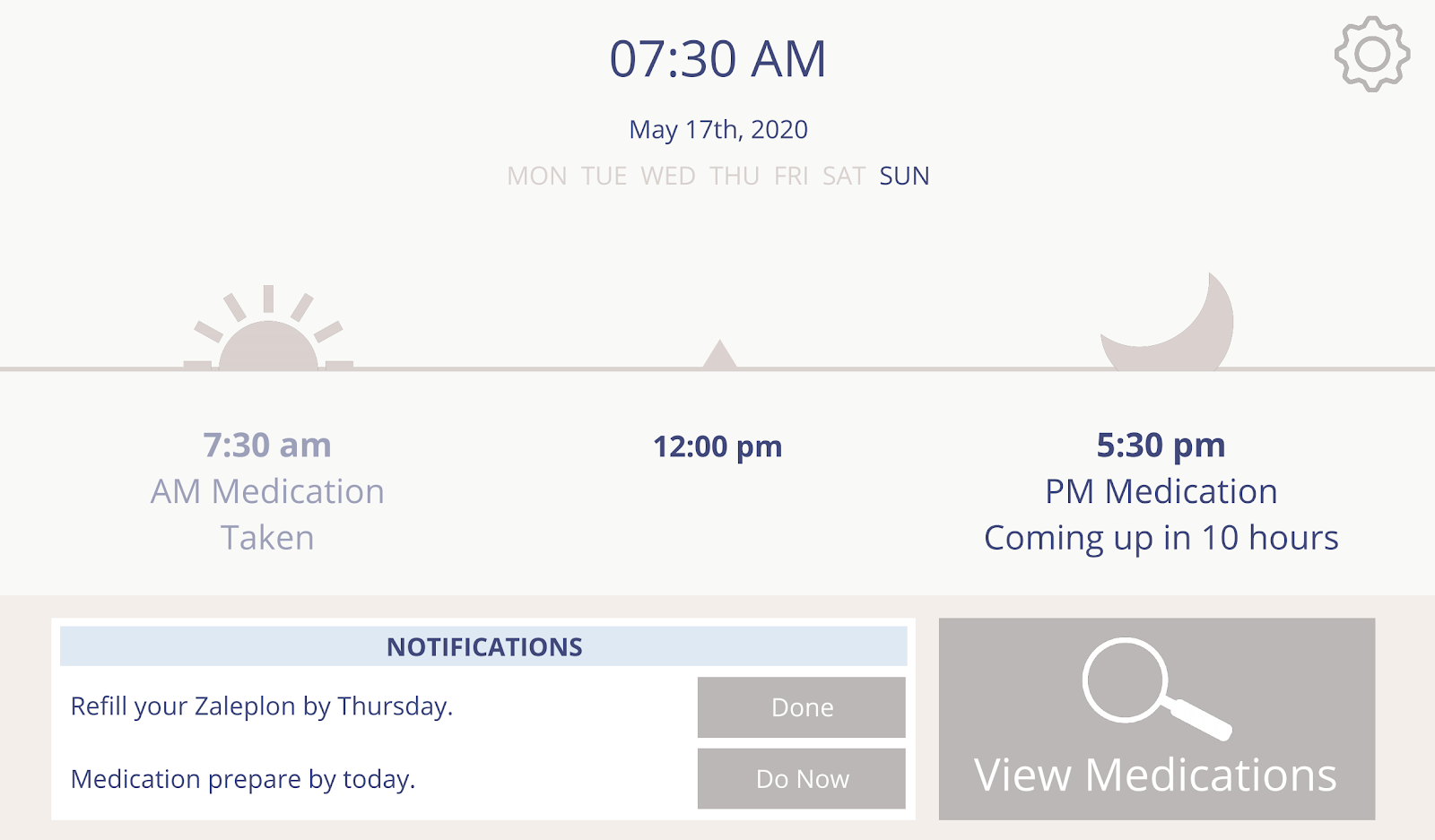

Unfortunately, around this time in the project is when we lost physical access to our users due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It would have been too slow to create physical prototypes, ship them to a single user, get feedback over video chat, ship them back, and repeat the process until we had enough feedback. Therefore we concentrated on creating digital prototypes that could convey the look, feel, feature set, and UI/UX of our concepts. Feedback sessions were held over Zoom when possible. We created a simulated user interface () for users to explore while we took notes.

Fortunately, we found a strong qualitative and quantitative signal in our feedback data showing that we were on the right track. The level of enthusiasm among caretakers, especially, for our solution was extremely high.