I am a big Neuralink fan. Brain-Machine Interfaces (BMIs) have been a fascination of mine for almost a decade. I even once used a device made by NeuroSky to make a ball move back and forth by meditating. This will very likely not be the last post about neural interfaces on this blog.

On Friday Neuralink gave a product update and demo over livestream. In some ways what they’re doing is very impressive and in some ways they’re a bit behind the cutting edge. I think it’s analogous to Tesla’s product strategy, in the sense that at the time Tesla was building the original Roadster the technology was not revolutionary, but Musk (while he slowly bought Tesla) and the other founders were able to build a solid platform for and culture of innovation while they also executed extremely well operationally. It turns out if you’re building cars and neural interfaces then operational excellence is a pretty good differentiator.

As with many potentially groundbreaking technologies, BMIs have a long history of speed-up/slow-down and people operating in a technological and ethical wild west.

The “biohacking” community, for the uninitiated, is a movement primarily among wealthy individuals in Silicon Valley to optimize their own body’s biology and especially their neurological function. Usually this involves taking a “stack” of vitamins, supplements, pharmaceuticals and things that should be classified as pharmaceuticals, all collectively called “nootropics”, or brain-enhancing substances. There’s some good science there, but there’s also a lot of risk, quite a few unknowns, and a telling lack of randomly controlled trials.

Biohackers don’t just focus on the brain, but there is a subgroup of that community, “neurohackers,” who do and who are often willing to try out some pretty extreme tech to enhance their brain function:

—Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation, or TDCS, almost literally boils down to attaching a 9V battery to the outside of your skull in order to bias certain neural pathways and enhance learning. It’s been studied for a long time with mixed results, but Halo Neuroscience appears to successfully be taking the technology mainstream.

—Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, TMS, is less commonly used by neurohackers because it involves much more bulky and expensive equipment. Dan Novy at the MIT Media Lab used a TMS machine to create programmable visual hallucinations, albeit at very low resolution.

—Looking forward to the promise of invasive neural interfaces, some people have taken matters into their own hands and travelled outside the US to have the devices installed in their own brains. Phil Kennedy is the most notable because he is an actual respectable neurologist.

The reason I’m giving this context is because what Neuralink is trying to do is the continuation of work that a lot of people have wanted for a very long time. Having Elon Musk working on this problem is bringing money, attention, and legitimacy to what much of the public would have otherwise not have taken seriously.

Before I dive in to the implications of Neuralink and modern BMIs, below is a bit of background on neural probes and why they’re very likely to be the path forward for the industry. If you want to jump to the design and philosophical musings, you can skip ahead a section.

Brain Machine Interface Primer

The task at hand is getting information into and out of the brain. In more conventional applications (mostly research, but also prosthetic design), the latter tends to be the more important. We can already take in megabits of information through our existing brain input streams, namely our eyes and ears. It’s not always easy to optimize data for human consumption, thus the art of data visualization, but we do OK.

Getting data out is much harder. Our highest bandwidth form of general data transfer out of the brain is speech, at a mere 39 bits/second (this number is remarkably consistent across languages). You can get better numbers by building specialized interfaces like the ones professional gamers use, but it’s debatable how much information is being transferred, and in any case those interfaces don’t generalize. Combine this with the fact that most live brain research is done in animal models, and the need for an interface becomes obvious.

Why invasive methods though? Why can’t Neuralink just invent a better version of the EEG that I used in my Mindball toy?

It’s a question of resolution. The brain operates on many length scales, from a single synapse (around 500 nm, or about 1/200 of a hair width) to an entire brain region (multiple centimeters). One cubic millimeter of brain matter has about 100k neurons.

Different technologies can capture different length scales, but all of the ones that can read from outside the skull tend to be limited to reading activity in a whole region. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) can actually get down to sub-millimeter ranges, but you have to be in a big tube full of spinning magnets and liquid helium. fMRI also measures blood flow, which is a good, but not perfect, lagging analog to neural activity.

Put in plain English: an EEG can tell whether I’m moving around and some basic information about my emotional state, but it can’t read the words I’m typing right now. Shout out to CTRL Labs for a clever workaround on that one using electromuscular data. There are other companies working on non-invasive BMI technology that hold a lot of promise, but I’m not going to take the time to delve into that here.

So, we probably need neural probes to do most of the fun stuff like play Starcraft with our minds or cure blindness.

The next question is: why the sewing machine?

Most neural probes are rigid, it turns out. It’s easier to fit more channels on a rigid probe, and you only have to insert one thing rather than a thousand. A 1024 channel rigid neural probe was announced earlier this year and one with almost 1000 sites (384 channels) on it is practically mass market.

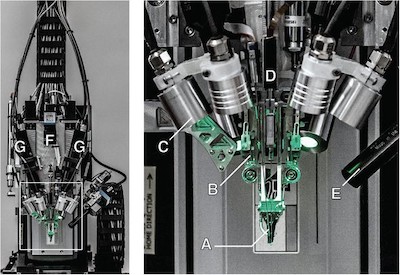

While Musk has said that he wants many thousands of channels, Neuralink is operating under the constraint of people actually wanting this device in their heads. Rigid probes break sometimes, and do a lot more damage when being inserted. One of the major points made at the announcement Friday was that the surgery would take one hour outpatient, and the probe threads were so small and inserted so accurately that the user (patient?) wouldn’t even bleed. All of this comes at the cost of needing to build a very complicated surgical robot/sewing machine to perform the thread insertion.

Design Implications

This is…new territory, to state the obvious.

Neuralink hasn’t released per-channel bandwidth specs, but we know a) that Elon wants “broadband” levels of data transfer, and b) that Bluetooth Low Energy, the communication protocol that’s currently (but almost certainly temporarily) being used, tops out at 2 Mbps.

However, having the Link installed is unlikely to allow you to “speak” to a computer 50,000 times faster than you can currently because while our brains have evolved a whole cortex to communicate with speech, sending data through a neural interface is going to be a new skill to learn, and will involve a bunch of inefficiency and loss.

That means that the first applications of neural interfaces will be specialized. You could install one to interface with the visual cortex, send it video data in some format, and perhaps the visual cortex will be able to learn to recognize the patterns. I’m both simplifying and up against the limits of my neuroscience knowledge, but it might be plausible because our brains are surprisingly good at adaptively interpreting new data input. Eg. if you see the world upside down for long enough, your brain quickly acclimates to it.

Let’s imagine for a second that the rather imposing technological and scientific hurdles are surmounted. Neuralink manages to make a device that allows you to interface with other devices and/or the internet in a high-bandwidth way.

One of the immediate concerns is privacy. Can someone literally read my thoughts? Or write malicious data onto my brain? Especially if the data connection is wireless, it’s a real concern.

It is possible that neural interfaces will fail for this reason. We do not have a good track record of keeping our devices secure, even our cars and pacemakers. There’s no reason to believe that neural interfaces will fare better. There are ways that we can design the systems defensively and intelligently, however:

—Don’t give the Link access to the open internet, at least directly. At a bare minimum camouflage neural data traffic by passing it through a smartphone first.

—Open source wherever possible. There will be intense attention and interest on making sure that the communications are secure. Open sourcing allows more eyes on potential vulnerabilities.

—Implement 2-Factor Authentication, or whatever version of the same idea applies to this situation. Make them hack you twice.

Nothing will be foolproof, but if we take security seriously, which it is hard to imagine that we will not, then it’s likely that the value of the interface will outweigh its risks.

So what can one do with a safe, secure, high bandwidth, consumer neural interface?

A lot, it turns out.

We won’t know for sure until people start playing around with it, but I have my own hopes:

—Emotional interfacing. The world of affective computing is trying to retrieve and manipulate emotional data using the currently available signals, but neural interfaces might give us access to the raw stuff. Ever wanted to understand why your political opponent feels the way they do? Or your significant other? We already convey emotion on top of our speech using inflection, but how much more depth and nuance might there be?

—Memory storage. What would a world be like where one could retrieve digitally anything they wanted to remember? How would that shape education or the workplace? How much more fulfilling would lifelong learning be if you could remember the context for each new piece of information consumed?

—Human-machine collaboration. This is a bit of a buzzword these days, referring to systems designed so that the human can do work that humans are good at, and the machine can do work that machines are good at. How much better could these systems be if humans and machines were directly coupled?

And I have a few fears as well:

—Without even hacking the neural interface, someone might manipulate the information we see in such a way that worsens echo chambers rather than collapsing them. This is, after all, what has happened with the first dramatic expansion in access to the internet.

—This could dramatically worsen class disparities. Any technology that costs money and gives more power and ability to the owner is going to be used to climb the economic ladder at the relative expense of those without it. We will need to be very judicious in our social and economic policy to ensure that this doesn’t spiral out of control.

—With increased access to each other and the world remotely, we may become even more physically distant. The social consequences of this trend are complex and still being uncovered.

I believe we can prevent the dystopian outcomes with intentionality, care and foresight, but we have to be going in with our eyes wide open.

The takeaway for designers of all kinds is that we need to be even more strictly human centered than we have before. This is a powerful new tool, but, I heard once, great power comes with great responsibility. We have to keep the interests of the user and all stakeholders front and center so that this new interface can save and improve lives.

Free Will

After we talked a bunch about Neuralink last night, my partner sent me an old fictional post by Scott Alexander of Slate Star Codex, which I’m copying here in full:

In the treasure-vaults of Til Iosophrang rests the Whispering Earring, buried deep beneath a heap of gold where it can do no further harm.

The earring is a little topaz tetrahedron dangling from a thin gold wire. When worn, it whispers in the wearer’s ear: “Better for you if you take me off.” If the wearer ignores the advice, it never again repeats that particular suggestion.

After that, when the wearer is making a decision the earring whispers its advice, always of the form “Better for you if you…”. The earring is always right. It does not always give the best advice possible in a situation. It will not necessarily make its wearer King, or help her solve the miseries of the world. But its advice is always better than what the wearer would have come up with on her own.

It is not a taskmaster, telling you what to do in order to achieve some foreign goal. It always tells you what will make you happiest. If it would make you happiest to succeed at your work, it will tell you how best to complete it. If it would make you happiest to do a half-assed job at your work and then go home and spend the rest of the day in bed having vague sexual fantasies, the earring will tell you to do that. The earring is never wrong.

The Book of Dark Waves gives the histories of two hundred seventy four people who previously wore the Whispering Earring. There are no recorded cases of a wearer regretting following the earring’s advice, and there are no recorded cases of a wearer not regretting disobeying the earring. The earring is always right.

The earring begins by only offering advice on major life decisions. However, as it gets to know a wearer, it becomes more gregarious, and will offer advice on everything from what time to go to sleep, to what to eat for breakfast. If you take its advice, you will find that breakfast food really hit the spot, that it was exactly what you wanted for breakfast that day even though you didn’t know it yourself. The earring is never wrong.

As it gets completely comfortable with its wearer, it begins speaking in its native language, a series of high-bandwidth hisses and clicks that correspond to individual muscle movements. At first this speech is alien and disconcerting, but by the magic of the earring it begins to make more and more sense. No longer are the earring’s commands momentous on the level of “Become a soldier”. No more are they even simple on the level of “Have bread for breakfast”. Now they are more like “Contract your biceps muscle about thirty-five percent of the way” or “Articulate the letter p”. The earring is always right. This muscle movement will no doubt be part of a supernaturally effective plan toward achieving whatever your goals at that moment may be.

Soon, reinforcement and habit-formation have done their trick. The connection between the hisses and clicks of the earring and the movements of the muscles have become instinctual, no more conscious than the reflex of jumping when someone hidden gives a loud shout behind you.

At this point no further change occurs in the behavior of the earring. The wearer lives an abnormally successful life, usually ending out as a rich and much-beloved pillar of the community with a large and happy family.

When Kadmi Rachumion came to Til Iosophrang, he took an unusual interest in the case of the earring. First, he confirmed from the records and the testimony of all living wearers that the earring’s first suggestion was always that the earring itself be removed. Second, he spent some time questioning the Priests of Beauty, who eventually admitted that when the corpses of the wearers were being prepared for burial, it was noted that their brains were curiously deformed: the neocortexes had wasted away, and the bulk of their mass was an abnormally hypertrophied mid- and lower-brain, especially the parts associated with reflexive action.

Finally, Kadmi-nomai asked the High Priest of Joy in Til Iosophrang for the earring, which he was given. After cutting a hole in his own earlobe with the tip of the Piercing Star, he donned the earring and conversed with it for two hours, asking various questions in Kalas, in Kadhamic, and in its own language. Finally he removed the artifact and recommended that the it be locked in the deepest and most inaccessible parts of the treasure vaults, a suggestion with which the Iosophrelin decided to comply.

Niderion-nomai’s commentary: It is well that we are so foolish, or what little freedom we have would be wasted on us. It is for this that Book of Cold Rain says one must never take the shortest path between two points.

I love this story. Scott does a great job creating a thought experiment that allows us to evaluate what this type of technology might mean.

The assumption that the earring always obeys your best interests is one that deserves skepticism. But let’s make a similar assumption that the meat computer in your neocortex also always obeys your best interests.

In both cases you have a computer acting in your best interests telling your body what to do. One is just a lot more effective than the other.

Practically speaking, you can never trust the earring fully, and nobody should be abdicating their free will entirely to something external. However, we unintentionally outsource decisions all the time, to our social networks, various behavioral nudges, Cambridge Analytica, etc. Even without going down too deep of a free will rabbit hole, you have to admit that any idealized conception of the population in 2020 making decisions purely as the result of critical thinking is absurd.

I would argue that the whispering earring is just a great smartphone with a really intuitive user interface. The internet already makes you demonstrably better at achieving the things you want! How often do you benefit from ignoring Google Maps while navigating? Or from writing code without access to Stack Overflow? I’m not saying that the internet has always improved our lives in every way, but without constant access to the entire store of human knowledge many of us would be unemployable, undatable, and stumbling through life.

If someone offered to put your brain in a vat that gives you the subjective experience of an eternity of the happiest bliss, would you sign up? Most people, including myself, would not. We value “authenticity”, which is definitely a word of our times. My apartment is covered in objects painted and dyed to appear worn down and “authentic” (I don’t actually own that).

Despite not wanting eternal bliss as a brain in a vat, we spend our whole lives working very hard and very ineffectively to try and achieve bliss anyway. We have a deeply embedded set of morals around work and achievement when it comes to deciding whether we deserve nice things. However, to some extent at least, we only see these as thresholds in relation to where we are now. The whispering earring person probably sees the brain in the vat as cheating themselves of a fulfilling life. We think using the earring is cheating. The Amish might think we’re cheating by using our smartphones. Maybe the Amish are cheating by retaining access to modern metallurgy.

To be fair to the Amish, I don’t think technology has made us happier. We’re all on the hedonic treadmill, but there are consequences to standing still while the treadmill is moving faster and faster.

A common theme that you’ll see me writing about is that we are standing at a threshold. The last 20 years have landed us right in the middle of a shoulder period of technological development. We’re entering a new regime.

Neural interfaces hold the potential to unlock some really important parts of that transition.